In late September, while speculation regarding the financial crisis dominated news outlets worldwide, the German media found itself distracted by a comparatively local story: the untimely death of Berlin Zoo employee Thomas Dörflein.

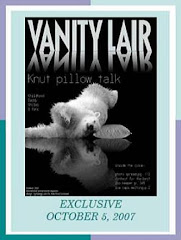

Dörflein was a man so beloved in his home city that he could hardly leave his apartment without being swarmed by groupies, but the real celebrity was his animal charge, Knut, a polar bear cub born in the Berlin Zoo in December 2006. Rejected at birth by his mother, Tosca, Knut lost his twin brother four days later to infection. Under Dörflein's care, the 810-gram whelp nonetheless became Berlin's first Eisbär to survive infancy in over thirty years. He enjoyed a prolonged period of international stardom—complete with action figures, product endorsements, theme songs, remixes, magazine covers, TV segments, and feature films—before maturing from plush toy to ferocious carnivore. Knutmania, as the press dubbed it, centered around the "Knut and Tom Show," a one-hour, twice-daily attraction during which Dörflein frolicked with his ursine protégé beneath the fusillade of appreciative cameras. The pair drew paparazzi and admirers from all over the world.

On September 22, the police found Dörflein's body in a friend's apartment in Wilmersdorf, a neighborhood in central-western Berlin. The cause of death: heart attack. Dörflein was 44. His girlfriend Gabriela Kaiser and two adult children survive him. Official press releases on the subject remained this terse. Yet in the days that followed, the emotional outpouring over Dörflein's death attained an intensity that shocked even me, a professed Knut enthusiast. "Everyone wanted to be like Thomas Dörflein," the popular tabloid BZ proclaimed. "He not only cared for Knut, he nurtured our desire to see harmony between man and beast." Berlin mayor Klaus Wowereit echoed the sentiment, publicly lamenting the city's tragic loss. "The residents of Berlin, the senate, and I myself received this news with great dismay," he wrote in a letter to Dörflein's mother. "It is incomprehensible that this great, strong, congenial man is no longer with us."

Within weeks, the Berlin Zoo created an annual award in Dörflein's honor. Their online Condolence Book registered 10,713 entries—some composed in rhyming verse, many several paragraphs long, festooned with emoticon-arabesques. YouTube was flooded with montage tributes. Still more striking were the "real" TV segments I caught online. Despite a prematurely frigid autumn drizzle, a steady stream of people turned up to pay their respects at Knut's enclosure, placing flowers, candles, and even propping condolence letters up against the glass. On Welt TV a camera lingered on an envelope addressed in capitalized red crayon to "DAD" before cutting to one badly shaken woman. Voice breaking, she told the reporter: "The worst thing about it was that it was just so sudden. We weren't…at all prepared."

Wir waren gar nicht drauf vorbereitet. At the time I found myself quoting this stuttered lament repeatedly to my German friends here in New York. Now, two months later, I am starting to understand my fascination. At one level, of course, the words are unremarkable, rote rhetoric of grief. We weren't ready, the Berlin native sobbed. Of course not: that's what death is. Yet her choice of phrase continued to haunt me. It still does, less because of the evident sincerity of her mourning than her puzzling tone of indignation. The untimely revival of Knutmania following Dörflein's death revealed that the bear-craze had been intended to prepare us for something. But what?

Read the whole article of Moira G. Weigel here...., the second part comes tomorrow...

Keine Kommentare:

Kommentar veröffentlichen